When Games Grew Up: An Ode to Final Fantasy Tactics

An upcoming remake gives us a reason to revisit one of the greatest stories in gaming.

I'm excited.

Final Fantasy Tactics (FFT)— a game from the PlayStation 1 era (1997/1998) — is getting a remaster. Or a remake. Whatever you want to call it, it’s happening. And that’s an incredibly cool thing.

I won’t spend much time here talking about the logistics — those details are still murky and better covered elsewhere. What I do want to talk about is why this game mattered so much in the first place.

Why the plot was phenomenal.

Why having complex and ambiguous characters meant so much.

Why it hit so hard at that age.

What Was Final Fantasy Tactics?

On the surface, FFT is exactly what it sounds like: a tactical RPG set in the Final Fantasy universe. But the label undersells the experience.

You control a party of characters, and battles unfold in turn-based combat — but this isn’t traditional Final Fantasy fare. This isn’t "pick an attack, pick a target, watch an animation, repeat." This is something more.

Here, you’re playing three-dimensional chess.

There’s terrain — not just left and right, but up and down. Obstacles that limit your line of sight (vision) and line of fire. Can't shoot arrows through walls. Chasms and deep rivers that limit how you move to approach the enemy.

There’s positioning, where elevation and direction relative to your target change the odds of success. Above and behind them? They'll literally never see you coming. In front of and below them? Good luck!

There’s turn order, dictated by character speed. And while you move and select an action in the same turn, the actions themselves have timing — some spells or attacks don’t land immediately. It’s entirely possible to move a mage forward to cast a spell, only for the target to act first, rush the mage, and kill them before the spell ever goes off.

Now imagine juggling this with a party of six.

Against a similarly sized (or larger) enemy force.

On battlefields ranging from wide open plains to narrow urban alleys.

It’s a lot. And I loved every minute of it.

Where Did Final Fantasy Tactics Come From?

This didn’t just materialize from the Final Fantasy ether. In fact, the game wasn’t even made by the same team behind the previous FF titles.

The real origin story begins with Yasumi Matsuno, the mind behind Tactics Ogre, an entirely different tactical RPG series. Matsuno worked at a company called Quest, where he’d made a name for himself crafting games with layered politics, moral ambiguity, and brutally honest narratives. Squaresoft — recognizing the brilliance — poached Matsuno and several of his key team members.

Matsuno: Let’s make Tactics Ogre… but set it in the Final Fantasy universe.

Square: Sounds great. But make sure to include chocobos and crystals so people know it's a Final Fantasy game.

And so FFT was born — a tactical RPG by way of political drama, dressed in familiar Final Fantasy garb, but speaking with a very different voice.

Final Fantasy + Tactics = So What?

It would’ve been enough for this game to just be good.

Tactical RPGs weren’t mainstream, but they had a niche following. Add in the Final Fantasy brand — fresh off the runaway success of Final Fantasy VII — and FFT was destined to sell a few million copies regardless.

If it had just been “Final Fantasy with grid-based combat,” that would’ve been fine. If it had just been “Tactics Ogre with chocobos,” it still would’ve been a fun time.

But it was more than that.

Much more.

And I don’t think anyone outside the development team knew just how much more it was going to be.

The Stories Are The Point

Let me step back for a moment.

I love games because they tell stories. Stories I get to participate in. They’re like books or movies or TV shows — they build worlds and pull you in — but unlike those, games let you take part. They invite you to be part of the story, not just a spectator.

For me, that’s always been the magic.

Super Mario World is fun. But without a narrative, it doesn’t hold me. I’m not here to chase high scores. I’m here to find meaning. I’m here to be in the story.

That’s why I fell in love with RPGs. They were the first genre that treated story as sacred. You didn’t level up because grinding was fun — you did it because the next boss fight was in your way, and the only way to see what happened next was to get stronger.

I came in through Final Fantasy IV and VI. Both told sweeping tales of war and identity, with big casts of characters and unforgettable setpieces. They had their share of nuance — some tragic villains, some tough choices — but at the end of the day, the structure was clear:

Here is your group of heroes.

There is the villain who wants to destroy the world.

Go stop them.

Simple. Satisfying. But morally black and white.

What I didn’t expect — what I wasn’t ready for — was what FFT did next.

The World of FFT Was a Complicated Place

Let me try to distill this — because this plot sprawls.

You play as Ramza Beoulve, youngest son of a powerful noble house. Your father commands a military order. Your older brothers will inherit everything. You, meanwhile, are a cadet-in-training — barely more than a squire — sent to put down a peasant revolt.

It seems simple.

Protect the nobility.

Keep order.

Don’t ask questions.

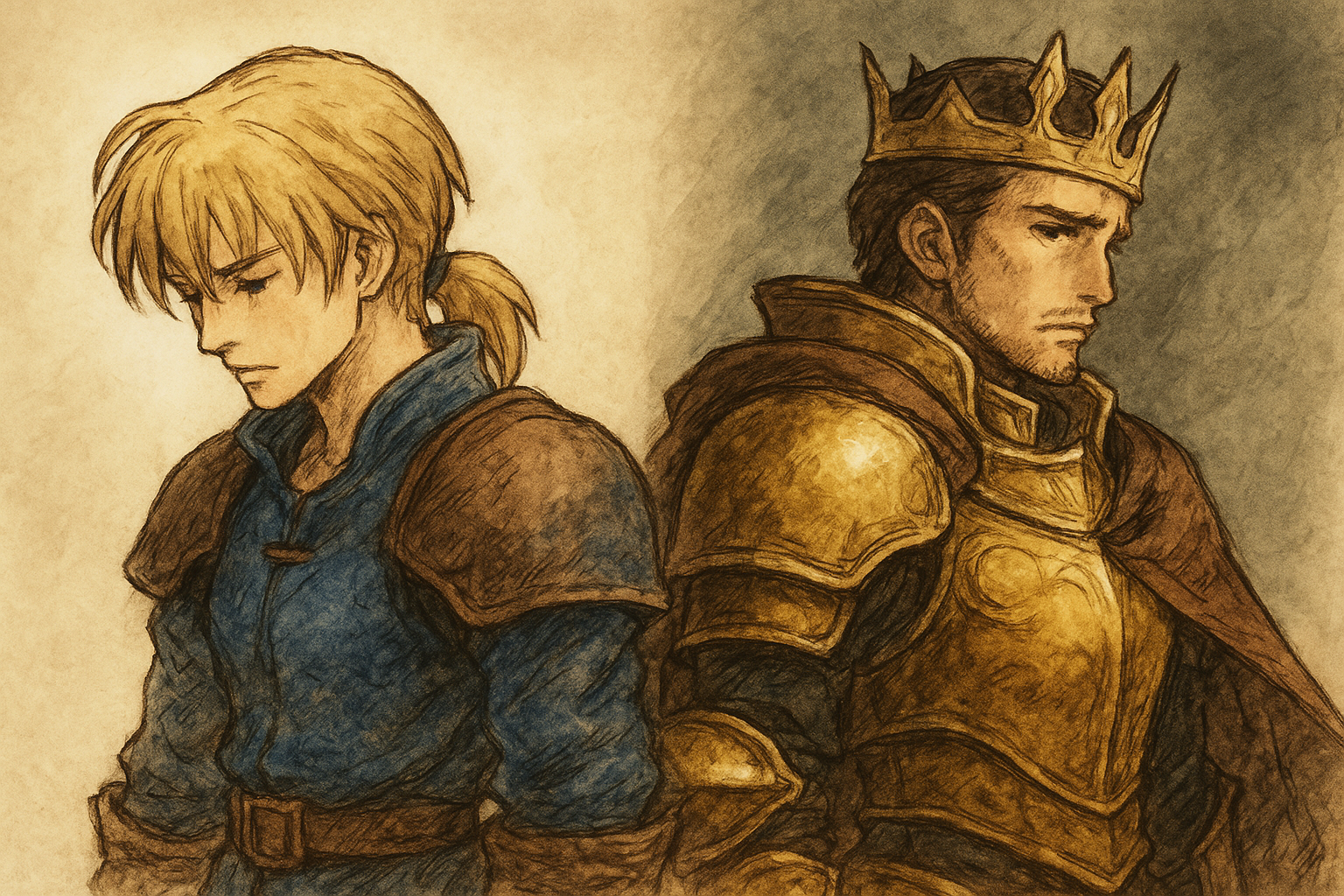

Beside you rides Delita Heiral — to others, he is nothing more than the son of a lowborn servant in your household, but to you? He is your best friend, your boon companion, your true brother. He trains beside you. Fights beside you. And when tragedy strikes — his sister is killed in the uprising — he leaves you.

And then the world starts to zoom out.

A war of succession erupts — two factions claiming the throne. It’s not just political. It’s personal. Families fracture. Ideals dissolve. Delita resurfaces, no longer a squire, but a rising player on the national stage — aligning with lords, manipulating nobles, doing whatever it takes to seize control of his fate. He plays the game. And plays it well.

Zoom out again.

The Church emerges, claiming neutrality. Seeking peace, an end to the bloodshed, to the war that is ravaging the continent. But you can see, they pull the strings from the shadows — shaping kings, rewriting history, feeding ambition. The war is a stage, and the Church holds the script.

Zoom out again.

Then come the Zodiac Stones — sacred relics, shrouded in myth, bound to saints of legend. Except… they’re not holy. They’re demonic. They house the Lucavi, monstrous beings who prey on human desire. The Church is not just complicit — it's possessed.

Ramza learns the truth. For that, he's excommunicated.

Branded a heretic.

Hunted by the Church.

Forsaken by his own family.

Delita, meanwhile, learns a different truth: that power lies not in fighting monsters — but in becoming one quietly enough that no one notices.

You do end up facing a world-ending threat, but not as a chosen hero or legend. Just as someone — the only one, really — who knows what's coming, and refuses to blink in the face of it.

You stop the end of the world.

And nobody thanks you. Nobody even knows.

Delita crowns himself king.

The Church buries the truth. Victors write the history.

And you fade into obscurity — unnamed, unknown, unmourned.

The game ends with a question. In the final scene — after murdering the queen he married to ascend the throne — Delita wonders aloud, "What did you get, Ramza? No one will ever know..."

He knew. And it ate him inside. Because while Ramza did what was right and lost everything, Delita did what was he thought necessary — and lost himself in the process.

A Complex Narrative at the Right Time

I was 15 when I played this game. Old enough to crave stories with complexity and nuance, but I didn't expect them from video games. I thought I knew what they had to offer — hero’s journey, fight the villain, save the world.

Instead, I got:

- Political betrayal

- Class warfare

- Religious manipulation

- Possession by forces unseen and unknowable

- A protagonist who is right… and punished for it

FFT didn’t hold my hand.

It didn’t give me easy choices. It didn’t offer moral clarity.

It gave me questions, but no answers. Expected me to see for myself.

It showed me that good men die. That the world isn’t fair. That history is a lie told by those in power. That doing the right thing may cost you everything — and still leave the world unchanged.

That’s what made it special.

That’s what made it formative.

FFT wasn’t just a good game. It was the first game – first example of any medium, really – that respected me enough to not sugarcoat everything, and trusted me to appreciate it as an adult.

The Game Wasn't Perfect

Was it flawless? No. Brilliance rarely is.

The original translation was clunky, sometimes incomprehensible.

The difficulty curve was steep and uneven.

If you are reckless, or even if you just get unlucky, you could permanently lose characters. Or time, if you hadn't saved often enough.

The polygonal graphics and 2D sprites haven’t aged gracefully.

But I still love it all the same.

The musical score remains one of the best in gaming. I still listen to it.

The job system was endlessly fun — you could build your party your way.

The world of Ivalice was rich, layered, lived-in.

There have been re-releases — on the PSP, on mobile — and a sequel aimed at younger audiences. That one wasn’t for me. It lost some of the grit. But that’s okay.

Because now — finally — we’re getting a real remaster. A chance to bring this story to a new generation, with the polish and reverence it deserves.

Why This Remaster Matters

FFT showed me that video games could be art.

That they could be political.

That they could be honest.

It didn’t pretend to be neutral. It had something to say. And more importantly — it had the courage to say it.

That’s why this remaster matters. Not just for nostalgia. Not just because it’s a classic. But because this game still has something to teach us.

About power. About truth.

About what it means to do the right thing — even when no one’s watching.

Even when no one remembers.